Obregon's Story

Obregon's Story

Eugene Obregon's ultimate sacrifice is but one example of the patriotism and loyalty demonstrated by the Latino American recipients of the Medal of Honor. Latino Americans have, time and again, shown their devotion to our country and to the ideals on which it was founded. But Eugene Obregon's story tells us something else about these Americans. It tells us that the divisions of race, religion or color have no place in an America in which a Latino from East Los Angeles can give his life for his friend - an Anglo from Texas. Truly, this is the brotherhood America is all about and the brotherhood we wish to celebrate..Below is Obregon's story as as told by William D. Lansford from interviews and Marine records. The story appeared on page 18 of the July 2001 issue of "Leatherneck - Magazine of the Marines."

Un Cuento Americano

"An American Story --

Gene Obregon Served Because He Owed It to Our Country"

William Douglas Lansford

The kid from East Los Angeles sat on the loader's side of the light machinegun, the helmet pushed back on his head, his profile outlined against a background of Korean sky and mountains. Opposite him sat the gunner, his face mirroring this rare moment of peace atop a ridge overlooking the Naktong River. Despite days of repeated attacks, the Reds had failed to regain the ground the Marines took from them, but they soon would be back to try again. Minutes later a Marine photographer strolled b,y and moved by the young gunners' battle-weary faces, aimed his camera, freezing the moment forever.

During the lull following the second battle of the Naktong, on this sweltering September day in 1950, Pfc. Ralph Summers and his assistant gunner, Pfc. Eugene A. Obregon, chatted, ate their C-rations, drank from their canteens, and generally did what Marines do when someone isn't trying to kill them. As darkness fell, both slid into the hole behind their gun to keep watch through the night. Like other men of George Company, 3d Battalion, Fifth Marines, they may have dreamed of home, of the lives they'd left behind. Neither dreamed that in 10 days they would assault a place called Inchon, and that 12 days later both would be caught in a storm of enemy fire, one to survive, the other to become a legend.

By any measure, G/3/5 has an extraordinary history, forged by extraordinary men. If Gene Obregon had not earned the Medal of Honor it's probable he would not stand out, but he did, and at a 50th anniversary reunion of George Co's graying warriors, a portrait of Obregon was prominently displayed beside the citation accompanying his award. That weekend, as the heroes of Pusan, Inchon and the Chosin Reservoir remembered, a story shrouded by the fogs of half a century gradually reappeared.

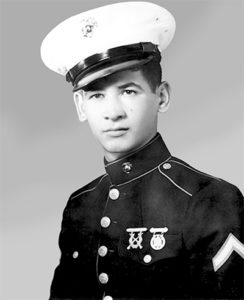

PFC Eugene Obregon's life was as all-American as an Andy Hardy movie. He had a father and mother who doted on him, an older sister who adored him, his own late model Plymouth coupe, and a dog named Spotty. To the students at Roosevelt High in East Los Angeles, he was a confident, slightly jug-eared kid who loved sports and smiled so engagingly that strangers instantly took to him.

While outgoing, he seldom let anyone get really close. One who did was Tony Medrano whom Gene met at Roosevelt High. "Both were good athletes," Marrujo, a friend from school, recalled. "Tony was a funny little guy but, like Gene, he was pretty feisty."

"They hit it off," smiles Virginia, Obregon's sister. "Tony hung around our house and we'd talk and talk and have fun. He and Gene were always together."

As Gene turned 17, he'd begun planning a future. He would do a hitch in the Navy, see the world, then come back and join the Los Angeles Fire Department.

Fate soon intervened. Richard La Carra, a Washington High baseball star, had joined the Marines right after graduating and now played for the base tean at San Diego. Resplendent in his dress blues, he began coming home on weekends, ostensibly to "visit the guys" but really to see Virginia. Gene, always protective of his sister, took stock of the 20-year-old Leatherneck and approved. Along with baseball, Richard talked Marines so enthusiastically that Gene decided to join the Corps.

Still five months shy of 18, Gene asked his dad's permission. With some misgivings, Pedro Obregon consented. "Gene said he owed it to our country," recalls Henrietta, his mother. "How could we refuse?" That June, Obregon left for San Diego to begin recruit training. Tony Medrano went, too. At the last minute he'd decided to enlist with Gene.

To no one's surprise, Obregon breezed through boot camp, qualifying as Expert with rifle and pistol. On 14 August 1948, Platoon 44 posed for its graduation photo. In the second row, Pvt. Obregon stands proudly behind a stern faced Pvt. Medrano. Within days, most of Plt 44 was assigned to the Fire Department at the Marine Supply Base in Barstow, California.

It was a pleasant two years. The firefighters were known as "The Barstow Fire Brigade" or "Gilson's Raiders" after Fire Chief Oliver C. Gilson.

"Our whole family drove to Barstow on weekends," Virginia remembers. "We'd take picnic baskets and spend the day with Gene and his buddies."

At 0700 one morning in July 1950, the fun ended. Master Gunnery Sergeant Robert E. Roberts remembered: "It was Saturday. I was getting dressed for liberty when the phone rang. When I identified myself I was told: 'You and the following men will pack your sea bags and fall out in 15 minutes. There are trucks waiting in front of the Orderly Room.' That was it. No time, no warning, nothing. We loaded up and went to Pendleton."

By August 1950, the war in Korea had gone from bad to worse. The U.S. Army, under-equipped and soft from five years of occupation duty in Japan, had been routed by the North Korean People's Army and was barely holding on to a tiny perimeter around the port of Pusan. Marines were pulled from bases, naval yards and supply depots. Even the brigs were emptied. The hastily assembled First Provisional Marine Brigade, consisting of two under-strength regiments, one artillery battalion and Marine Air Group 33, all under command of Brigadier Geneneral Edward A. Craig, had barely eight days to ship out for Japan. Training would have to take place at sea.

In Pendleton, the Barstow Marines, who'd been so close since boot camp, found themselves adrift. Roberts, Frank Torres, Medrano, and many others went into rifle companies and in the preparations to integrate and ship out, most of them virtually disappeared from Obregon's life. "It was as if somebody dropped a hand grenade in the middle of us," Torres recalled.

On 14 July 1950, Craig's brigade sailed out of San Diego, bypassed Japan and docked in Pusan. Just weekslater George Co and Obregon werein the front lines in Changwon, one of the first Marine units to fight in Korea. En route to Korea, picked on by tough, old Technical Sergeant Harold Beaver (who, it turned out, had been a prisoner of war on Corregidor), encouraged by his patient Section Leader, Sergeant Joe Musto, and the pleasant, 19-year-old first gunner, Ralph Summers, Obregon had learned "the gun," and begun working up from carrying ammo to firing it. By the second Battle of the Naktong, Ralph Summers and Gene Obregon were seasoned machine gunners, and crusty, old Beaver didn't seem too displeased with the results.

Now the young Marine sat unmoving, his mind calm despite the activity outside. Like other Marines crammed into the bodies of the tracked landing vehicles (LVTs) that carried the assault wave, he sought the suspension of all thought, for in the state of nothingness lies the control of fear. It's something every combat veteran must learn: how to confront danger with indifference.

It's 0630 hours, 20 Sept., and eight miles beyond the river barrier lies the final objective, the city of Seoul.

The air exploded with the roar of engines and clattering steel as the six LVTs of the first assault wave crawl into the Han River, churning their way to the far shore. The enemy is alerted. Their mortar shells and artillery dotted the river and their small arms fire clanged against the armored amphibians. The men of Co G clutched their weapons tighter and tried not to think that minutes from now they would be fighting for their lives.

Aware that the Marines were massing in the night, the North Koreans waited for the "Yellow Legs" to make their move. Now a wave of what seemed like floating tanks was coming across, under a storm of rockets and napalm from the blue, gull-winged planes and a hellish din of mortars, artillery and small arms fire. As the noisy vehicles crawled ashore, the "Yellow Legs" came pouring out, firing and charging up the hillsides to engage the defenders in a fierce assault. Panicked and overwhelmed, the Reds gave way, then ran.

As Lieutenant Colonel Robert D. "Bob" Taplett's 3/5 regrouped, Captain Robert D. "Dewey" Bohn's George Co settled in, studied the terrain ahead and got ready for a counterattack. Speed seemed prudent, for the North Koreans didn't take kindly to humiliation.

In his command post 500 yards away, LtCol Raymond Murray, Commanding Officer, 5th Marines, noted on his map that G, H and I Companies now held Hills 95, 51, and 125. His 1st and 2nd Battalions would be across by late afternoon, with the attached Korean Marines following. Further south, Colonel Lewis B. "Chesty" Puller's 1st Marines was moving on Yongdungpo. In two days of fighting would overcome resistance, cross the Han, and enter the southernmost edge of Seoul.

Among the replacements assigned to Co G prior to sailing for Inchon was PFC Bert M. Johnson, whose duties during a year of service included stints as a clerk-typist, M.P., and Navy Yard Guard. Bert was 19 and hailed from Grand Prairie, Texas, a small farming community. Obregon, born in Los Angeles, was also 19, and through one of those quirks of fate the lanky kid with the Texas twang (said to be partial to beer, payday poker, and sassy girls) and the straight-arrow Mexican-American became friends. "We were inseparable," Bert told a reporter. "I thought as much of Gene as I ever thought of my four brothers."

By 23 Sept., Col Homer L. Litzenberg's 7th Marines, newly landed at Inchon, were following the commanding general, First Marine Division, Major General O.P. Smith's directive to cross the Han and approach Seoul from the north. For the first time since arriving in Korea, MajGen Smith had his entire Division together and all seemed well. But in the mountains four miles west of Seoul, Murray's advancing 5th Marines had run into a buzz saw.

Judging by his performance at Inchon, North Korean Major General Wol Ki Chan was not a very good commander. Overwhelming force and surprise notwithstanding, he had let the Marines in too cheaply, lost contact with his units as the Marines moved east, quickly lost Kimpo Airfield, and only minimally employed the Han River as a barrier. However, Chan knew the mountains and it was there that he meant to stop the 1stMarDiv.

In subsequent intelligence reports it would be noted that on 20 Sept., as LtCol Murray's 5th Marines was crossing the Han, MajGen Chan was moving his 25th Brigade and his 78th Independent Regiment into positions atop the rugged hills that surrounded northwestern Seoul like a wall of dragon's teeth. This area was a maze of bunkers, observation posts, and gun positions covering the eastern approaches. If that failed, Chan's final line of defense would be inside Seoul, itself. He had 20,000 troops and ample materiel at his disposal, and he was ready to use them. When the Americans arrived, they'd find there wasn't a safe route to be had.

On 22 Sept., Capt Francis I. "Ike" Fenton's B/1/5 secured Hill 105S, and on 24 Sept., after two days of bloody battling, D/2/5 broke the enemy's main line of resistance on what would be called "Smith's Ridge," named after the Dog Co commander, H. J. "Hog Jaw" Smith who died in the final charge.

Obregon had survived nearly two months of combat. His letters were now about George Co. He never wrote of the hardships or dangers, only about how well he ate, how safe he was, and how he got all the "easy jobs" while others did the fighting.

However, on 24 Sept., Obregon wrote that Tony Medrano was dead. "I saw him die," Gene told Virginia, without explaining where, or how. But it was clear Gene was devastated.

The letter bore one other sad distinction. It was the last one Obregon would ever write.

The terrain feature on which MajGen Chan had anchored his defenses was the massive Hill 296, on the northwest edge of Seoul. Shaped like a huge outspread hand with its fingers pointing southeast, south and southwest, 296 was critical to control of the area. Its ridges were designated "No Name," 105 North, 88, Smith's Ridge and 104. If one followed the "thumb" ("No Name," actually a branch of 105N) to level ground, one would be in the outskirts of Seoul. This was exactly what MajGen Smith hoped to do and MajGen Chan meant to prevent.

Late on 21 Sept., LtCol Taplett's 3/5 had occupied the top of 296, but casualties on both sides were appalling and holding it would be another matter.

Atop Ridge 105N, Item Co, passing through How Co, was pressing the assault supported by automatic fire and mortars from George Co on its right flank on the slope below.

The fighting on the ridge could be clearly seen by the men of George Co as How Co continued its attacks, withdrawals and counterattacks. The Reds' defense lay astride the shaggy ridge. Every time How Co leathernecks charged, there was a hellish din, smoke and fiery explosions of white phosphorous, and people on both sides popping up and running around until somebody dropped them. Air strikes and supporting fire by the 11th Marines devastated the Reds' defenses, but somehow they hung on. In the midst of this, calls kept coming in for Capt Charles D. "Charlie" Mize, the new CO, to help the hard-pressed troops above with more machinegun and 60mm mortar fire, as if George Co wasn't already giving them all they had. By nightfall little progress had been made. The Marines dug in, in place, and as a bonus, the North Koreans pelted them with mortar fire all night.

Finally, the 5th Marines were free to enter Seoul. Retired Master Sargeant (then PFC) Robert "Squint" Snyder, G Co's clerk, whose office seemed to be in the middle of the nearest battlefield, recalled the morning of the 26 Sept.: "About 0600 I was standing on a ridge with Lieutenant [John] Westerman. He'd been hit a few weeks back and had just rejoined us the night before. Well, he raised his hand and yelled, 'Move out!' and then he dropped. Damned if he hadn't been hit again." Finding that "Big Jack" was unconscious, Squint yelled for a corpsman, then went down to join TSgt Beaver's machine guns, which were moving out in trace of 3rd plt, George Co.

That morning, the men of Co G had awakened to miserable prospects. They'd been on that stinking hill for three lousy days and things were about to get worse. Beaver, now the ranking officer in Weapons Plt, was yelling for them to "Saddle up!" Moments later, they went stumbling down the slope leading to the outskirts of the city.

The narrow trail through the brush that covered 105N like a scabrous growth was invisible at times, and the advance of the leathernecks was slow, with the men of Sgts Joe Musto and DuWayne Philo's machine gun sections vainly trying to get comfortable under the weight of their guns, ammo boxes, rifles, packs and whatever else they carried.

The first dirt road with a scattering of mud hooches gradually broadened into a cobblestone street with walled, tile-roofed houses on both sides. Ahead, where Col Puller's 1st Marines was attacking, Seoul was in flames, and the sound of fighting was incessant. What slowed the progress of Puller's tank-infantry teams was a series of massive rice bag emplacements along every street, sewn with mines and defended by mortars, anti-tank guns and automatic weapons. This was MajGen Chan's last hurrah, and it would be remembered as "The Battle of the Barricades." George Co's descent into the capital was cautious, as they moved downhill along a dusty road dotted with clusters of mud hooches. The silence was spooky, interrupted by an occasional sniper or a grenade tossed at the advancing column.

"After a while," Sgt Philo recalled, "if we heard anything, we'd lob a hand grenade or empty a clip into the place." In one case, they kicked a door in, surprised 3 Reds with a machine gun, and made short work of them.

The next street they took was paved with cobblestones and consisted of larger houses. After a climb, it descended to what looked like a dead end. Protective walls lined the left and a shallow rain ditch the right. Still in two columns, Beaver's Weapons Plt kept moving, unaware that somewhere along the way they'd lost the rifle platoon.

"I had the tripod," Summers remembers. "Obregon carried the gun. Dick Sullivan and his guys were on the left and Bert Johnson [Summers' first ammo carrier] was up ahead. The rest of our section and DuWayne Philo's were strung behind us, with Beaver and the corpsmen." It was almost noon. No one realized that, as they'd followed the unfamiliar route, an error had occurred that would have tragic consequences.

Capt (later MajGen) Mize later recalled: "A small but significant gap developed between Company G that was attacking through a built-up area in the city and Company I that was attacking along a ridge above the built-up area. It was into this gap that Technical Sergeant Beaver's unit mistakenly advanced."

What seemed like a dead end of the street was actually the foot of Ridge 105N entering the city. On the side of it the Reds had built a large barricade to guard their flank and the Weapons Plt was headed right for it.

The first indication of danger was a sniper's shot, followed by a storm of automatic fire that sent Marines scurrying in all directions. "I felt like I'd been kicked in the hip," recalls Summers. "Then I fell on the street. The first shot had hit my right leg and I was bleeding like hell."

Drawing his .45-caliber pistol, Summers jumped over a low wall into a small yard and looked back trying to assess the situation. Everything was confusion. Besides the zinging, ricocheting small arms fire, mortar shells were landing all over, men and equipment lay scattered by the surprise attack. Obregon's machine-gun tripod was in the street, surrounded by ammo boxes. Fifty yards ahead, he lay prone with a useless machine gun and his .45-cal. pistol still in his holster. As yet, no Marine had fired back. PFC Bert Johnson, making a dash for cover, had been hit by a burp-gun and lay in the middle of the street, with wounds to his head, arm, elbow, leg and ankle.

No one knows what motivated Obregon. Perhaps he was thinking of Tony. Perhaps he remembered the friends he'd lost.

Those closest heard him yell: "Hang on, Bert. I'm coming!" Then Johnson yelled back: "Stay where you are!" And Obregon again: "I'm coming to get you, Bert!"

They saw Obregon suddenly jump up and run down the middle of the street, firing his pistol. In plain sight of the enemy, he grabbed Johnson by the collar, dragged him to the ditch, and began bandaging his wounds. When the enemy charged, Obregon emptied his pistol at them, then picking up Johnson's carbine and shielding Johnson's body with his own, he began firing again.

"The North Koreans were coming out," one Marine remembered. "It looked like a platoon shooting at Obregon, who kept shooting back." At one point Obregon glanced at Johnson and seemed to say something.

"I was up on the crest of the street," Snyder recalls, "and I could see Obregon firing. When his carbine was empty, he dropped it, pulled a grenade from his belt and threw it at them. That's when the machine gun got him."

Hit twice in the face, Obregon died instantly. But the other Marines had rallied and moved in, killing the remaining North Koreans.

Obregon's final battle had lasted but a few minutes. Amazingly, he, Summers and Johnson were the only Marine casualties, but an entire enemy platoon had been wiped out and the Reds' flank breached.

"I received from Technical Sergeant Beaver the first spontaneous report of Obregon's gallant action," Mize wrote later. "Within minutes thereafter, I recall a number of members of the unit sadly, but proudly repeating to me the courageous deeds of Private First Class Obregon. During my combat tour in Korea I remember no other heroic action being reported so vividly and spontaneously to me and certainly not by so many."

On 27 Sept. 1950, TSgt Harold Beaver and the men of G/3/5 raised the Stars and Stripes over Government House in Seoul.

"We got our first hot chow that night," Bob Roberts remembers, "and we got to sleep in the building. But we still wore the same dungarees we'd worn since Inchon. Next day they moved us out of town. I guess we smelled bad."

On 30 Aug. 1951, Mr. and Mrs. Pedro Obregon were invited to Washington D.C., where they received their son's posthumous Medal of Honor from Secretary of the Navy Dan A. Kimball. Staff Sergeant Bert Johnson, recovered from his wounds, also attended.

Asked later what Obregon had said to him during the shooting, Johnson replied: "He told me, 'Bert, if we're going down, we'll go down fighting like Marines.'"

Editor's Note: As a Marine sergeant with Carlson's Raiders and an Army officer in Korea, Bill Lansford acquired 18 awards and decorations and a lifelong interest in guerrilla warfare. His first book, "Pancho Villa," was made into a major motion picture by Paramount Studios. Since then, Lansford has authored many movies, TV shows, magazine stories and articles. The Marines are still his favorite subjects.

In our restless times, when racial differences are often exploited to pit us against each other, the Board of the Eugene A. Obregon/CMH Memorial Foundation decided that this young Marine's story and that of the other brave Latino CMH recipients should be told. And so we established the goal of erecting a monument to these Latino heroes in the heart of downtown Los Angeles, so that not only Latinos, but all Angelenos and visitors to our city will be informed of their sacrifices.

We want to celebrate the brotherhood of all Americans. But we also need to provide a source of pride for young Latinos; an opportunity for them to know that their heritage is a noble one; that they, too, are valuable and equal members of this American society.

We ask you to become a part of this important story. Please join us in making the Eugene A. Obregon/CMH monument a reality.